Stories We Love

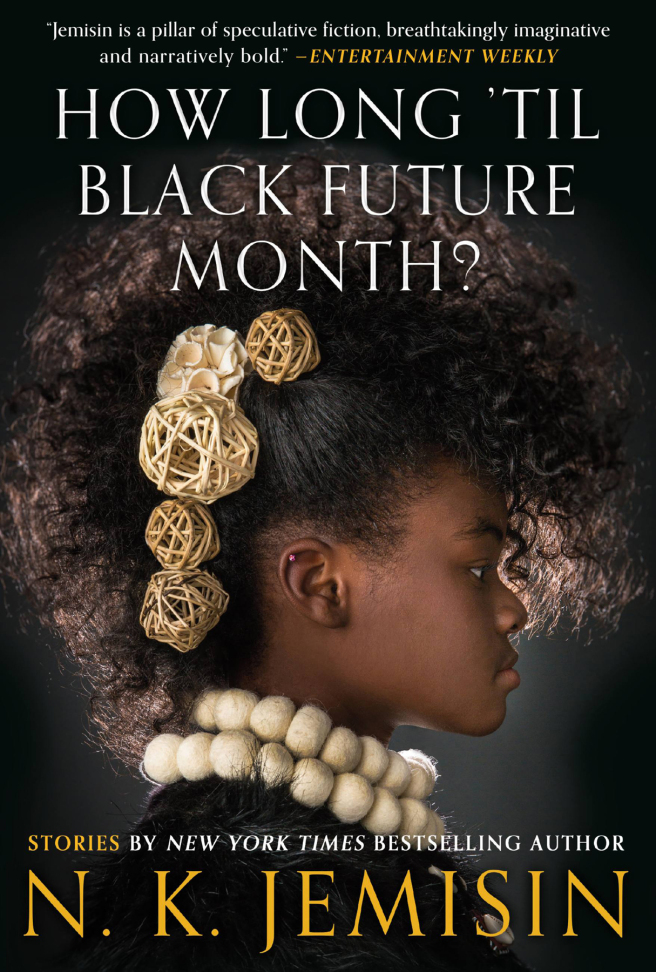

N.K. Jemisin’s “The Ones Who Stay and Fight” is the opening story in the author’s short story collection, How Long ‘Til Black Future Month. The story introduces the collection, as does the book’s title, as a work of fundamentally utopian sff.

“The Ones Who Stay and Fight” was written in conversation with “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” [pdf], Ursula K. Le Guin’s own challenge to utopia, published in 1973. “Omelas” has been discussed extensively (a recent article on “Omelas” and its utilitarian implications for our own times can be found here) and this review will side-step a comprehensive comparison of “Omelas” and “The Ones Who Stay and Fight”. Instead, the focus here is on Jemisin’s story, its conception of systemic violence, its implicit sense of justice and hope, and how Jemisin’s vision applies to the fight against climate change.

Some readers familiar with both stories may have hoped that N.K. Jemisin’s “The Ones Who Stay and Fight” would reject the “necessary” violence of the previous story. Readers could have been comforted, after all, by a utopia that harms no one and specifically rejects violence perpetrated against innocents. But both Le Guin’s and Jemisin’s stories contain harm to a child. In Jemisin’s story, the child is harmed as a side-effect of preserving utopia. But rather than remain in isolation, as in “Omelas,” Jemisin’s child is cared for — and ultimately educated to become a part of the community mechanism which preserves utopia in Um-Helat. The important distinction between Le Guin’s story and Jemisin’s is that Jemisin’s system protects Um-Helat from inequality and injustice, whereas Le Guin’s system is a quintessential example of these things.

Rejection vs. Revolution

Le Guin is lauded for complex social commentary in fiction and for her speeches calling for systemic change, but “Omelas” is a product of its time in that its politics suggests an ability to walk away from the injustices of society. To reject one’s culpability in the system and live separately from that which ultimately benefits us. Of course, if all residents of Omelas walked away, the system would collapse. But within the scope of the story, no mass movement is evident and the child continues to be tortured.

Jemisin’s “The Ones Who Stay and Fight,” then, is a story for this time. The ethic of the story is that one cannot absolve oneself of the responsibility for the system under which one lives, and while one might not be able to change it, one must stay engaged in one’s community and fight for change. What does this fighting look like? In “The Ones Who Stay and Fight,” the child who is harmed through the loss of her father is tended to, educated, and initiated into the enforcement wing of the society which protects Um-Helat from anti-utopian changes. The girl grows up as a powerful figure standing between Um-Helat and the creeping ideologies of injustice. The girl, rather than being locked powerless in a closet, is given agency to address that which harmed her by fighting against its root cause.

While the figure of the child in Le Guin’s story remains isolated and without hope for a different life, the child in “The Ones Who Stay and Fight” remains entrenched in her community. For the child, the community will never be quite the same, never again a perfect utopia. She lost her father and through this loss learned of violence in Um-Helat of which she was previously unaware. But change in Jemisin’s story comes not through a rejection and a walking away, but through the care of one’s community and becoming an integral part of its protection.

Jemisin’s Utopia and Climate Change

While Jemisin’s story does not specifically address climate change, it presents a model of address to any encroaching injustice. Climate change will affect future generations more than most people alive today. Those of us enjoying the benefits of a Western, fossil-fuel economy are living at the grace of a system which keeps a child in the closet — millions of children. The time for walking away from the problem and absolving ourselves of guilt is over. In opposition to this idea of rejection and isolation (and through these things, absolution), Jemisin’s story shows us how to care for the future. It is an imperfect process. It is a process that does not, and cannot, avoid harm for all. But working toward the holistic justice of engaged community and relationship as a way to care for the future is humanity’s best hope.

1 thought on “Review: “The Ones Who Stay and Fight” by N.K. Jemisin”