Black Lives and Environmental Justice

By now everyone is aware of the recent international uprisings against police brutality and systemic oppression. If you are somehow not aware, see Mapping Police Violence for an overview of violent police actions against primarily Black people. The data, though not yet updated for 2020, shows that police violence is largely unconnected to the prevalence of crime in a specific place. The reason for that violence goes much deeper than specific incidents to which police respond. Black people (and their allies) are rising up now to confront a long history of violence.

There have been some social media rumblings about this moment as a distraction — from pandemic lockdown, from restarting the economy, from addressing climate change. But we must not be distracted from how all of these things are connected. In this moment we must attend to the suffering of Black folks. We must attend to the ways that their communities are sites of both the quick and aggressive violence of the state, as in police brutality, and the slow violence of poverty and climate change — violence that is “neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive, its calamitous repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales” (Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor).

This is a moment to make these connections and acknowledge and expunge that which feeds a violent system. The following are a collection of articles which connect racial injustice to the environment and environmental movements. Each of these articles demonstrates that necessity of approaching the problem of the environment with a broader, more inclusive vision of justice.

3 Ways Racial and Environmental Justice Are Connected, as Explained by the Vision for Black Lives

This article raises the facts that Black people have less access to renewable energy solutions such as solar panels and wind turbines, and are disproportionately affected by the waste and pollution produced by fossil fuels. The article also calls for more Black representation in politics, arguing that automatic voter registration is a way to increase political engagement at all levels of government.

The Climate Movement’s Silence

If you have ever attended a meeting for an environmental group and found yourself sitting amidst a crowd of white faces, it may be because mainstream environmentalism has long refused the connections between racial and environmental justice. This article describes a problematic segment of environmental movements — people whom the article labels “Climate Chads” — whose voices drown out those of Black environmentalists and shape movements toward whiteness. Environmental movements must address with the fact that addressing climate change means reckoning with the ways that movements shut out Black participation.

Responding to protests, green groups reckon with a racist past

This article details how environmental groups emerged from a foundation of racism — ideas of conservation that primarily functioned for white leisure in nature, or to preserve nature for the use of white people only. Early environmentalists were often overtly racist, espousing eugenics and sterilization for Black people (as well as Indigenous people and non-Black People of Colour) as a solution to overpopulation. While the article does highlight some statements made by environmental groups indicating that the focus is moving from conservation to an environmental justice which includes racial justice, the fact remains that the environmental movement’s racist past must be addressed and atoned for.

I’m a Black climate expert. Racism derails our efforts to save the planet

In this article by marine biologist and policy advisor Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, she quotes Toni Morrison who says that “The very serious function of racism … is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.” Racism keeps Johnson and others from attending to the work of environmental stewardship and research, from giving climate change their full attention. Johnson also cites a statistic indicating that both Black and Latinx people are significantly more concerned about climate change than white people are, and imagines the power of a climate movement that includes those voices and that energy. Johnson calls for white environmentalists to become actively anti-racist in order to include Black people in the climate fight.

Stelliform and Amazon

In 2018, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos was interviewed about Amazon’s success and its impact on Bezos’ space travel company, Blue Origin. In this interview, Bezos was quoted as saying:

The only way that I can see to deploy this much financial resource is by converting my Amazon winnings into space travel. That is basically it.

Jeff Bezos, Amazon CEO

Amazon and Labour

We love space travel and space research, but there are a lot of problems with this statement. Firstly, Bezos displays a shocking lack of imagination for someone with so many resources. He actively undermines his workforce when he clearly has the money to pay them more. Amazon’s warehouses in the midst of the pandemic are increasingly sites of unsafe contact, which Amazon workers protested on May 1st. Amazon’s response to union organization among its workers is to quibble about sick leave, remove union literature and fire organizers who agitate for health and safety improvements in the workplace.

That Bezos refers to the money Amazon makes as “winnings” demonstrates an understanding of economics divorced from human labour and the human lives his policies affect. That Bezos looks to space before tending to those affected by his choices on Earth is a grave failing.

Amazon and the Environment

Attending to its responsibilities on Earth would mean first taking stock of the ways that Amazon’s business choices are ecologically unsustainable. Amazon has not disclosed the information needed to get a complete picture of its environmental record, but various non-profits have done that work and ranked Amazon in the public interest. The Guardian collected rankings from Climate Counts, The Carbon Disclosure Project, and Greenpeace‘s How Clean is your Cloud report and found Amazon ranking among the worst environmental offenders. In this article, BuzzFeed reporter Nicole Nguyen details the ways in which Amazon Prime’s shipping contributes to emissions, traffic congestion, and waste, while locking consumers into a system that is undermining public delivery services.

Amazon and Publishing

When our editorial team first spoke with other local publishers, we asked “is it necessary to have our books on Amazon?” The resounding answer was “yes.” But we’re committing to revisit this question for the reasons listed above and because of the effect that Amazon has on small publishing.

When people buy books from our website, we receive 100% of that money. From that money, we buy our printed books and supplies, pay our authors and artists, and invest in marketing and publicity. When people buy from Amazon, we may receive 50% or less of the money we would for a direct order. Under Amazon’s model, we publish and publicize less, and authors and artists get paid less for their work. For many small publishers, having their books listed on Amazon costs them money.

Our Statement on Amazon

At this time, we are selling our books on Amazon. Amazon has many negative impacts on our society, but it also provides some good: quick delivery of essential items for people with disabilities, or cheaper items for those who can’t afford to shop elsewhere. Amazon also provides some semblance of legitimacy for new authors. These authors need to be accessible to their readers at a central web location, not relegated only to the small-press-corners of the Internet. While we hope you will choose to support us and our authors by purchasing books from our website, it is important for our books — and our ideas — to be available to a wider public, which is access that Amazon provides. Indie publishers are beginning to make dents in this monolith. This is work to which we will contribute as we grow.

When Revolution’s Too Quick and Shallow

Michael J. DeLuca’s novella, NIGHT ROLL, is scheduled to be published in October. The book does an excellent job of expressing both the joy and struggle of rebuilding community after loss. In this blog post, DeLuca considers the message NIGHT ROLL brings to a post-pandemic world.

The Future from Before the Pandemic

by Michael J. DeLuca

In 2017, thinking of 2020, I started writing a novella about everything that was scaring me then: climate collapse and its vast, unforeseeable array of consequences; anthropogenic mass extinction; systemic racism and environmental injustice; scorched-earth capitalism. The real, existential threat of white nationalism hadn’t yet sunk in. Global pandemic hadn’t even crossed my mind.

Some of this novella I wrote at three in the morning. My baby wasn’t yet sleeping through the night, so neither was I. Let’s be honest, I was beside myself with sleep deprivation–but also with fear for his future. Also at three in the morning, I wrote my Reckoning 2 editorial, mourning the future he could have had, acknowledging that I had no choice but to build one where he could thrive.

NIGHT ROLL comes out in October, just before my 41st birthday. It was always a bit of an alternate history; certain technology and certain impacts of climate change are just a little bit accelerated, for dramatic effect, and because of my aforementioned fears. Now, in some ways, it’s a fever dream of what might have been.

A new, single mother comes to Detroit fleeing sea level rise and refugee crisis on the East Coast, where I’m from. Lonely and isolated, she’s forced to seek community and support, like I was. She’s forced to invest in a place she doesn’t understand, where a lot of people far worse off than she is have been struggling to survive for a lot longer. And despite odds, despite the city’s crumbling infrastructure and indifferent, disaster-capitalist kleptocracy, she finds acceptance, love, family, and a future.

I turned in final edits on March 13th of this year, the day before my family went into pandemic isolation. My partner teaches—among other things, media literacy—at a large public university about an hour north of Detroit. Classes have gone all-online. I always worked from home. The kid is three, practicing letters and numbers at our kitchen table, learning to ride a trike, eating anise hyssop and mint poking up out of the spring snow in the yard. We’re fine, we’re safe. We donated our pandemic stimulus, and then some, to food banks and advocacy for immigrant children.

Shortly after we moved here, I was introduced by the documentary “American Revolutionary” to the work of civil rights activist and community organizer Grace Lee Boggs, then approaching 100 years old. In the movie, she talks about how the work of justice is never done. She rejects the idea of revolution, despite the word being right there in the title, as too quick and too shallow. She’d been doing this work in Detroit for fifty years, through water shutoffs, white flight, Black neighborhoods bulldozed to build overpasses, helping build Detroit’s urban farming renaissance, helping build community and resilience that don’t depend on infrastructure or prosperity. Grace died in 2015, but I know what she’d have wanted us to do: listen to each other, take care of each other, keep learning, keep working.

A lot of the science fiction coming out in the next years runs a risk of looking cozy and quaint next to these real, live dystopian horrors. And no doubt many of those writers are afraid for their own future. I’m lucky enough, privileged enough, that my family doesn’t depend on income from my creative work for their survival. But I want to think of this pandemic, this time in which we’re all simultaneously isolated and sharing a profound experience of grief, trauma and radical change, as the greatest opportunity for the triumph of the human imagination I’ve ever experienced. How will we remake ourselves? Science fiction has always been touted as a literature of ideas, of possibility. This is its chance to be that in ways we’ve never seen.

I hope NIGHT ROLL still has the capacity to inspire, despite being set in a world where people can still hug strangers in the street. I’m confident in its message.

Detroit is suffering horribly right now. Good people are dying. But it will rise again. It always has.

When the World is Changed in an Instant

In September, Stelliform will publish its first book, Depart, Depart! by Sim Kern, a cli-fi ghost story which considers Jewish and trans experiences intertwined with the changes wrought by climate destabilization. Climate change as a whole is slow, but some of its effects can change the world on a scale of minutes or hours. Not unlike the experience of a global pandemic.

In this post, Sim Kern writes about the links they see between experiences of climate change and experiences of the pandemic.

COVID-19 and Depart, Depart!

During a crisis, human beings aren’t great at long-term thinking. In a fight-or-flight response, our brains block out everything but the most immediate source of danger—literally giving us “tunnel vision.” Like many writers, I’ve struggled to put words on the page the last few weeks, as I’ve wrestled with pandemic tunnel-vision. I write about climate change, and even though I understand the links between COVID-19 and environmental destruction, even though I’m aware that the suffering and death caused by COVID-19 is a fraction of what unchecked climate change will bring, I’ve still felt like, “maybe now’s not the time to harp on climate change.”

But as it’s become clear that the virus is here to stay, the danger of this tunnel vision becomes increasingly apparent. Some politicians are seeking to worsen social and environmental injustice, on the grounds that we can only afford to think about the virus right now. For example, under the pretense of addressing the pandemic, conservatives have attempted to restrict abortion access in 32 states, and the Trump administration is seeking to allow doctors to discriminate against trans patients. Meanwhile, The United States’ Environmental Protection Agency has drastically relaxed environmental regulations for polluters, even though studies have shown that air pollution is linked to a higher death rate for COVID-19. And in most places, exposure to air pollution correlates with racial and economic inequality.

So as people committed to social and environmental justice, we can’t afford virus tunnel-vision. We must continue talking about these critical issues, especially in the midst of a pandemic. We need to be louder than ever on the importance of racial, economic, and LGBTQ inequality. And, terrifying as it is, we need to keep imagining the climate-changed future, until there is overwhelming pressure to act. And so I’ve never been more proud to be represented by Stelliform Press, which prioritizes narratives at the intersection of climate change and social justice.

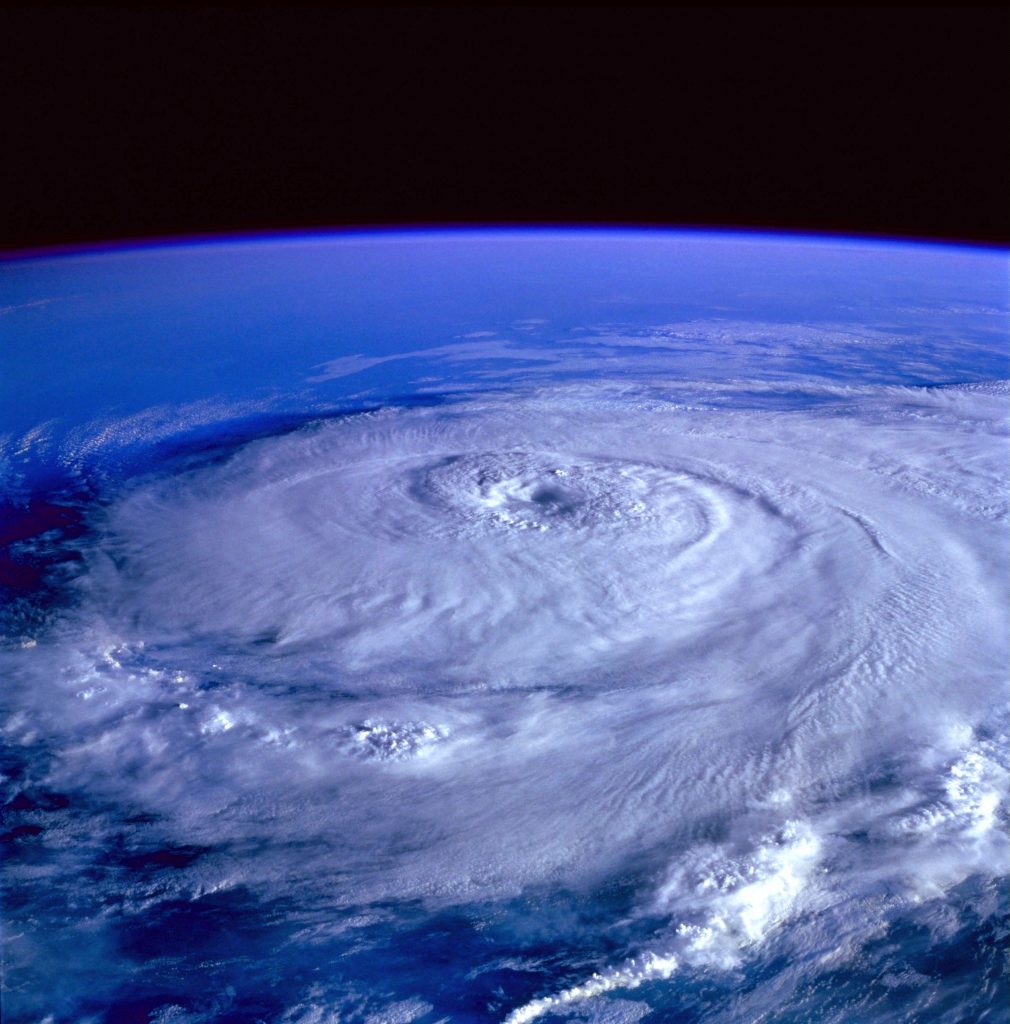

In my forthcoming novella with Stelliform, Depart, Depart!, a massive hurricane devastates the city of Houston. Noah Mishner must shelter in the Dallas Mavericks’ basketball arena, where he fears that being trans and Jewish puts him at risk with some “capital-T” Texans. To make things worse, he’s being haunted by the child-ghost of his great-grandfather Abe, who escaped from Nazi Germany in a duffel bag.

Rereading Depart, Depart! for the first time since the pandemic has been a surreal experience. I did not foresee a deadly virus in Noah’s future, and if I had, it might’ve robbed him of those few moments of normalcy and connection he’s able to find in the arena. Building relationships with other climate refugees might be far more difficult in the wake of a natural disaster if social distancing is simultaneously being enforced.

Still, despite the lack of a pandemic, Noah’s story feels more relevant than ever. Houston is currently bracing for a worse-than-average hurricane season. As the Gulf of Mexico warms, I worry the storm I dreamt up is all too likely. Inside the Dallas Maverick’s arena, class, racial, and LGBTQ inequalities are worsened by a natural disaster, just as they have been by COVID-19. And in the story as in our nation, gun-toting conservatives terrorize people who are just trying to survive in the name of “freedom.”

Above all, Depart, Depart! is about those moments when the world changes in an instant. When you’re forced to leave your old life behind, what do you take with you? How do you hang on to your identity and community? And will you hold fast to your humanity, even when survival is on the line? These are questions we’re all grappling with during this pandemic. We’ll continue to grapple with them as the climate crisis intensifies. Literature that fortifies us, and helps us prepare for that crisis, is more vital than ever—and I hope Depart, Depart! can be counted among those titles.

Earth Day 2020

Every year, Earth Day affords an opportunity for us to collectively take stock of our relationship with the environment. The first Earth Day fifty years ago is the result of one such stock-taking. Environmentalists were inspired by the “Blue Marble” photo — an image which still reverberates through Western culture with nearly the same potency as when it was first viewed. About this photograph, Ursula K. Heise writes:

Set against a black background like a precious jewel in a case of velvet, the planet here appears as single entity, united, limited, and delicately beautiful. Thinkers as diverse as media theorist Marshall McLuhan and atmospheric scientist James Lovelock were deeply influenced by images such as this one; neither McLuhan’s notion that the world had turned into a global village nor Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis of the Earth as a single superorganism can be dissociated from its impact.

Ursula K. Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet

The “Blue Marble” photograph inspired a globalist perspective shift, which comes with both positive and negative ramifications for environmentalist culture. One one hand, the globalism inspired by the “Blue Marble” makes tangible the sense that we all exist together on one planet. Seeing the ecosystem of the entire Earth — visible in the way the clouds curl across the atmosphere or the ways ocean currents stretch from one continent to another — makes connection real. On the other hand, connection does not indicate sameness. The cultural shift inspired by the “Blue Marble” was an erasure as much as it was a widening of perspective. We do not experience our environments in the same way. We do not all have equal access to the Earth.

What perspective can Earth Day afford us now, during these quarantine-times, when the view of our planet is less from the porthole of a spaceship in orbit and more from a closed front door or an apartment balcony? The view is certainly less expansive these days.

But maybe it is a good time to take a step back from the globalist viewpoint and pay attention to environments close to home. To examine the ways we interact with environments in our own cities, in our own homes. To think of our relations with humans and non-humans alike and consider how our connections on a small scale can be shifted toward sustainability not only in an environmental sense but in all the ways that we relate.