Michael J. DeLuca’s novella, NIGHT ROLL, is scheduled to be published in October. The book does an excellent job of expressing both the joy and struggle of rebuilding community after loss. In this blog post, DeLuca considers the message NIGHT ROLL brings to a post-pandemic world.

The Future from Before the Pandemic

by Michael J. DeLuca

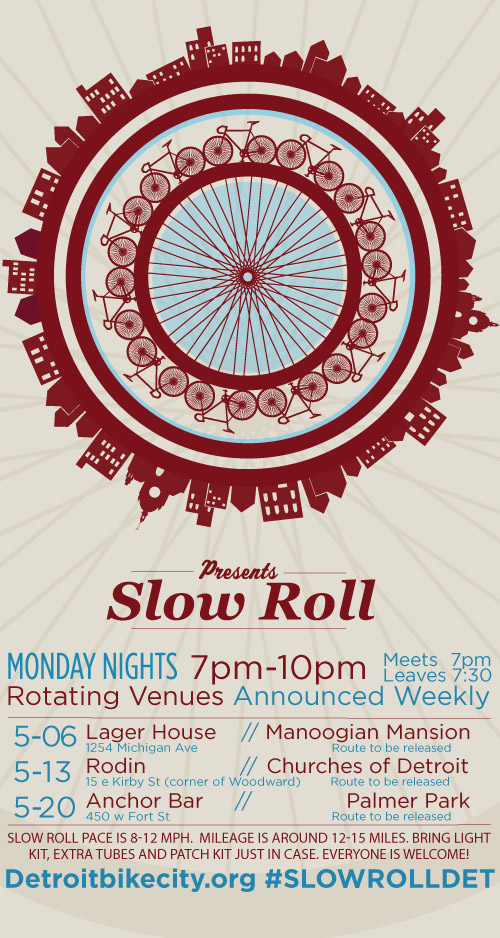

In 2017, thinking of 2020, I started writing a novella about everything that was scaring me then: climate collapse and its vast, unforeseeable array of consequences; anthropogenic mass extinction; systemic racism and environmental injustice; scorched-earth capitalism. The real, existential threat of white nationalism hadn’t yet sunk in. Global pandemic hadn’t even crossed my mind.

Some of this novella I wrote at three in the morning. My baby wasn’t yet sleeping through the night, so neither was I. Let’s be honest, I was beside myself with sleep deprivation–but also with fear for his future. Also at three in the morning, I wrote my Reckoning 2 editorial, mourning the future he could have had, acknowledging that I had no choice but to build one where he could thrive.

NIGHT ROLL comes out in October, just before my 41st birthday. It was always a bit of an alternate history; certain technology and certain impacts of climate change are just a little bit accelerated, for dramatic effect, and because of my aforementioned fears. Now, in some ways, it’s a fever dream of what might have been.

A new, single mother comes to Detroit fleeing sea level rise and refugee crisis on the East Coast, where I’m from. Lonely and isolated, she’s forced to seek community and support, like I was. She’s forced to invest in a place she doesn’t understand, where a lot of people far worse off than she is have been struggling to survive for a lot longer. And despite odds, despite the city’s crumbling infrastructure and indifferent, disaster-capitalist kleptocracy, she finds acceptance, love, family, and a future.

I turned in final edits on March 13th of this year, the day before my family went into pandemic isolation. My partner teaches—among other things, media literacy—at a large public university about an hour north of Detroit. Classes have gone all-online. I always worked from home. The kid is three, practicing letters and numbers at our kitchen table, learning to ride a trike, eating anise hyssop and mint poking up out of the spring snow in the yard. We’re fine, we’re safe. We donated our pandemic stimulus, and then some, to food banks and advocacy for immigrant children.

Shortly after we moved here, I was introduced by the documentary “American Revolutionary” to the work of civil rights activist and community organizer Grace Lee Boggs, then approaching 100 years old. In the movie, she talks about how the work of justice is never done. She rejects the idea of revolution, despite the word being right there in the title, as too quick and too shallow. She’d been doing this work in Detroit for fifty years, through water shutoffs, white flight, Black neighborhoods bulldozed to build overpasses, helping build Detroit’s urban farming renaissance, helping build community and resilience that don’t depend on infrastructure or prosperity. Grace died in 2015, but I know what she’d have wanted us to do: listen to each other, take care of each other, keep learning, keep working.

A lot of the science fiction coming out in the next years runs a risk of looking cozy and quaint next to these real, live dystopian horrors. And no doubt many of those writers are afraid for their own future. I’m lucky enough, privileged enough, that my family doesn’t depend on income from my creative work for their survival. But I want to think of this pandemic, this time in which we’re all simultaneously isolated and sharing a profound experience of grief, trauma and radical change, as the greatest opportunity for the triumph of the human imagination I’ve ever experienced. How will we remake ourselves? Science fiction has always been touted as a literature of ideas, of possibility. This is its chance to be that in ways we’ve never seen.

I hope NIGHT ROLL still has the capacity to inspire, despite being set in a world where people can still hug strangers in the street. I’m confident in its message.

Detroit is suffering horribly right now. Good people are dying. But it will rise again. It always has.