Review: E. Catherine Tobler’s THE NECESSITY OF STARS

E. Catherine Tobler’s upcoming novella from Neon Hemlock, The Necessity of Stars, is a unique take on a climate changed world and what it takes to live within it.

UN diplomat Bréone Hemmerli lives in the protected enclave of the Irislands estate. There, she cares for her gardens, visits with her companion Delphine, and attempts to broker peace while dealing with memory loss. When she meets an alien named Tura in her garden, she begins to learn new ways of being in the world, and new ways of returning to her former self.

There have been many books that approach a story from the amnesiac’s perspective. Often it’s a plot device used to catch a reader off-guard. The device is sometimes used to artificially withhold information until a crucial moment. But in The Necessity of Stars, Bréone’s memory loss is integrated into the environment. Bréone is isolated from the dying world. She is protected by her status as a UN diplomat, but also vulnerable as an elderly woman. There is a sense, then, that Bréone’s enclave is also vulnerable – that, like her memory, the protected gardens around her could fall to the ravages of climate change which advance outside of Irislands.

But the permeability of Bréone’s environment and the sense of danger that brings is also a source of hope. Bréone is open to this hope because of her condition: were she not vulnerable due to persistent memory loss, she would not have been so open to Tura when he appeared, nor to the solution that Tura presents to both the problem of a climate-ravaged world and the forgetfulness of an old woman. Vulnerability, then, is key in The Necessity of Stars; it is an opening through which all in Bréone’s world must pass – and by implication all in our world as well.

Near the end of the novella, Bréone tells herself:

Memory is a form of fiction.

E. Catherine Tobler, The Necessity of Stars

Memory is a story you tell yourself, a story that keeps the days threaded together in proper order. Experts in memory function say your first memory probably never happened, that it is a fiction you’ve told yourself so many times you’ve simply come to believe it as truth.

This novella offers a story about created worlds: the damaged and dying world created by industrialization and unfettered capitalism, the worlds we create in our own minds (to escape said world or, sometimes, to justify it), and the created world that is possible if we are vulnerable and open to the kinds of changes that move us through discomfort to something new. In her characteristic lush and intricate prose, E. Catherine Tobler highlights the necessity of change and the inherent hopefulness in vulnerability.

Review: Hummingbird Salamander by Jeff VanderMeer

Jeff VanderMeer’s Hummingbird Salamander is a departure from his last few novels: a realist thriller about “Jane Smith,” a woman who finds a taxidermied hummingbird and through this discovery becomes embroiled in an “ecoterrorist” plot.

VanderMeer is known for his female protagonists; his most popular series was one that was helmed by four female scientists. But Jane Smith is VanderMeer levelling up. Smith is unusual in a lot of ways, but also relatable. The progression of her perspective and her values throughout the novel is one that, I think, VanderMeer intends to stand in for the kind of growth that most Western people need to achieve in order to create an integrated relationship with their environment. Her “otherness” — her unconventional appearance and her history which means that she is always a little aloof, set apart from others — ensures that she is uncomfortable enough to seek change and accept it when it comes to her.

In this review, I focus on Jane Smith, who shows the reader “how the world ends” but also how it is always beginning again and could begin again, if we let it. If we respond to the invitation.

Jane Smith and the Power and Responsibility of the West

Readers may pick up on the name VanderMeer’s protagonist chooses for herself — a name with the anonymity of a “Jane Doe” but without the unidentified corpse connotations. Instead of a dead woman, VanderMeer’s “Jane Smith” is the maker of her surname, someone who makes things happen (both intentionally and unintentionally). This distinction is the thrust of the novel. “Jane Smith” speaks not from an unconditionally dead world. She speaks from a dying world, but one which still possesses the potential to be made and remade. One which the reader is invited into, and invited to be a part of.

But before any invitation can be accepted, the reader must contend with this protagonist — and her connections to the Western status quo — as she is. Jane Smith is a large, strong woman. Her body and her experience of living in it tangibly affects both her perspective and how others perceive her. VanderMeer writes a protagonist that observes how others look at her and is constantly aware that others are troubled by her appearance and presence. Additionally, Jane Smith is troubled within her body, observing that, like a bear, she is “always injured” in contending with the power of her body.

Unlike a bear, though, Jane’s power and her injuries are connected to a history of abuse. She uses the power of her body in a way that responds to that history, though over the course of the novel she realizes that she embodies the violence that her grandfather inflicted upon her in a way that is sometimes similarly cruel. I came to see Jane and her power as representative of an American position within Western power. She is a part of that power that has separated from her ancestry, but abuses power in sometimes similar ways: she uses violence to influence people and abandons those to whom she should be responsible. Jane has the opportunity to use her body differently, but falls into the patterns she learned from her progenitors.

Jane Smith and the Invitation

Hummingbird Salamander is a thriller. As a protagonist in a thriller, Jane Smith collects clues and gradually reveals the full scope of the situation she finds herself in while experiencing persistent threats to her life and the lives of those she cares for. Each clue she discovers is an invitation to another kind of understanding. But Jane’s key revelations, and thus her responses to these invitations, are always late. She spends months hiding out in a houseboat, and then in a mountain wilderness hiding from survivalists and militiamen. By the time she makes her way to the next phase of her journey, the journey has moved on without her.

Is it a stretch to make a connection between the missed invitation, the lateness of response, and our collective Western response to climate change? Maybe. But Jane misses opportunities because she isn’t yet prepared to understand, or she’s healing from wounds inflicted upon her, or she is occupied with tasks she thinks will help but don’t. It struck me that Jane Smith missing invitation after invitation, and realizing only after it is too late, after so much has already been lost, is us. Jane Smith is a warning.

Hummingbird Salamander is an invitation. VanderMeer begins the book at Chapter 0, as if he needs to go back to some place before one, before the reader gets wrapped up in the quick-moving action of the story, to make the invitation distinct and clear. He uses the second person pronoun “you” to invite the reader specifically into the story and its journey of discovery and the shifts in perspective that are provoked. At the end of the novel, Jane Smith is faced with her last choice (and skip this em-dashed phrase if you are concerned with minor spoilers) — to transform herself beyond her previous transformations, to risk death in a way that finally invites life — and her response is extending that invitation to the reader as well. Through Jane Smith, VanderMeer addresses us directly and invites us to take up the most necessary journey of our lives.

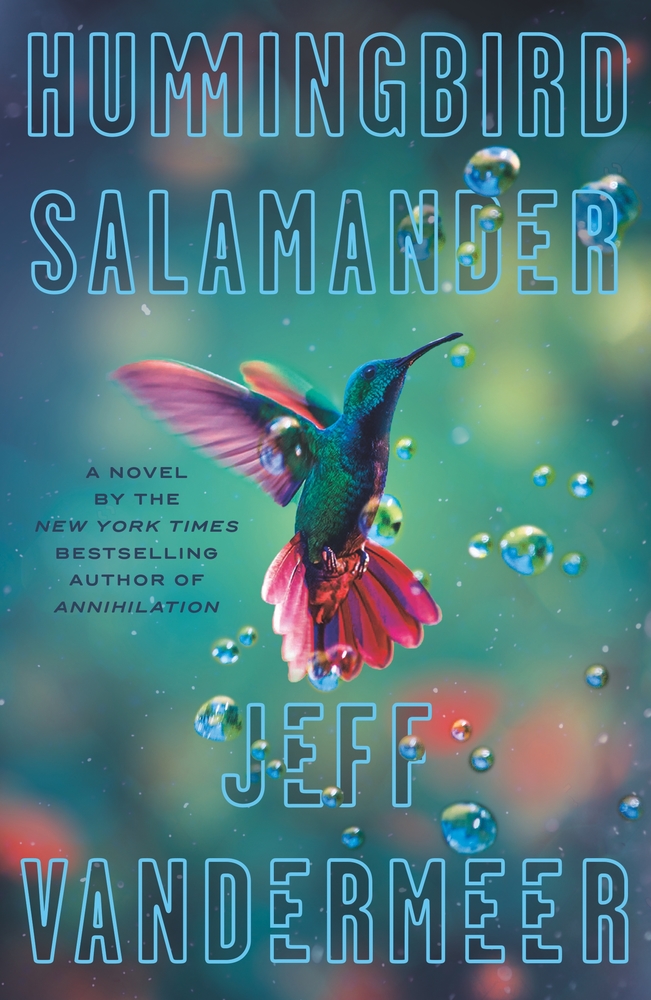

Cover Reveal: Cynthia Zhang’s After the Dragons

We’re pleased to reveal the cover of After the Dragons! To be published on August 19, 2021, this is a first novel for publisher and author alike. The cover art is by Chinese Canadian artist Wang Xulin, with design and typography by Yu-Lobbenberg Rachel, who also did the art and design for Octavia Cade’s The Impossible Resurrection of Grief. This cover reveal is in tandem with Locus magazine, which featured Zhang’s book on their Twitter and Facebook feeds, as well as in their newsletter.

Cynthia Zhang’s After the Dragons is now available for pre-order here.

About the Book

Cynthia Zhang’s After the Dragons is a queer science fantasy — that is, a story based on scientific ideas, but with fantastic elements — set in Beijing. In this book, researcher Elijah Ahmed and activist Xiang Kaifei join forces to save the city’s beleaguered dragons and find a cure for Kai’s illness. Grief hangs over their relationship and Eli and Kai must confront hard truths if there is any hope for themselves or the dragons.

This is a tender story, appropriate for readers interested in the effects of climate change on environments and people, but who don’t want a grim, hopeless read. The novel is beautiful and challenging, focused on hope and care, navigating the nuances of changing culture in a changing world.

Don’t miss any After the Dragons news, giveaways or events! Sign up for our newsletter here:

Advance Copy Giveaway Contest! (Now Closed)

📢It’s time to give away some advance copies of Octavia Cade’s THE IMPOSSIBLE RESURRECTION OF GRIEF!🎉 This contest is open to anyone, worldwide. It will run from Friday March 12 – Friday March 19 2021. Winners will be announced March 20.

How do I enter the contest?

The contest is on our Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. To enter the contest, follow us + like and share posts on any platform. Report any follows, likes, and shares on the contest post on any platform. Multiple entries are allowed and encouraged!

How to get the most entries

🎟️🎟️2 entries for a newsletter sign up here.

🎟️🎟️ 2 entries for a share/retweet on any platform

🎟️1 entry for a follow on Twitter, on Facebook, or Insta

🎟️ 1 entry for following @OJCade on Twitter

🎟️1 entry for a contest post like on any platform

If you do ALL THE THINGS you get 15 entries!

Be sure to report your entries on the contest posts here or on FB or Instagram. Honor system applies! On March 20, we’ll randomly select 5 winners. Good luck to all! We can’t wait to send this beautiful book out into the world!

Contest Post Quick Links

Access the contest posts here:

Update

We randomly selected our 5 winners on March 20 and 5 copies of Cade’s novella are now making their way across Canada and the United States. Congratulations to the winners!

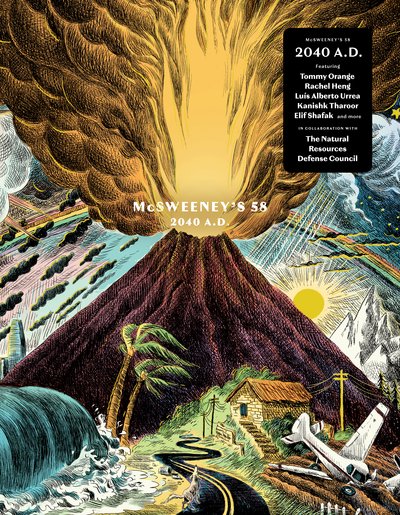

Review: “The Rememberers” by Rachel Heng

This post is the second in a series of short reviews about individual stories from McSweeney’s 58 Climate Fiction issue. The first post, on Mikael Awake’s “The Good Plan” is here.

The focus of this review is “The Rememberers” by Rachel Heng. Heng is the bestselling author of The Great Reclamation (forthcoming in 2022) and Suicide Club (2018). Born and raised in Singapore, and now living in Austin, TX, Heng has fiction in The New Yorker, Best Small Fictions, Kenyon Review and many other venues.

“The Rememberers” is set in a future Singapore in which society has been upended by sea level rise. Encroaching water is kept at bay by the sea wall, but many are left unprotected in the decommissioned zones. The “lucky” ones are buried in stories-deep underground apartments which make room for the privileged on the surface but deprive most of fresh air and sunlight.

In this beleaguered society, the Ministry recruits members of the older generation to recount their childhood stories, including details about the location and description of buildings, schools, relationships, and day to day life. With this information, fed into a developing algorithm, the Ministry hopes to find the link between the old way of life and the new. But for Ma, the narrator’s elderly mother, remembering — a process which brings memories to life for the rememberer — becomes a reason to live in a world she barely recognizes and which promises only exponential upheaval.

Like Mikael Awake’s “The Good Plan” (reviewed here), Heng’s story makes memory a crucial element in successfully bridging the chasm between a pre and post climate change world. For Ma, the memories she relates of her childhood, of the people she cares about, and the places she loved, give the present day meaning. When she is removed from that — through memory loss due to Alzheimer’s, through the displacement of her home to an underground bunker, and the subsequent loss of community — she becomes destructive.

The ending of this story was a surprise; despite the increasing disorientation and destructiveness exhibited by Ma as she rails against her personal memory loss and her removal from the Ministry program, I was not expecting that violence to be taken up by the narrator. Upon further reflection, however, it is difficult to see another path forward for this family which has been literally buried alive. The Ministry has taken Ma’s memories and now denies her the comfort of those long-ago experiences. In this way, memory is a resource which the state harvests and uses with the same indifference as it did water, wood, metals, and fresh air. The narrator’s violence at the end of the story is drawing a boundary, demanding an end to the careless use of resources, which includes the people who are otherwise discarded.

I wonder how intentionally Heng positions Alzheimer’s disease as a metaphor for how we experience the climate changed world. Ma no longer recognizes her changed surroundings as home, despite the fact that she is surrounded by her furniture and other belongings. For her, the experience of the new world is one of uncanny displacement and as she becomes increasingly agitated she destroys those belongings which link her to her former life. The narrator’s violence at the end of the story, then, could be read in two ways. First, that she is resisting the commodification of memory by the state and insisting on humane treatment; or, perhaps the narrator becomes an agent for her mother and her memories, destroying that which comforts and placates, thereby demanding real solutions to environmental catastrophe. There may be other ways to read the ending to this poignant story and the nuanced precedent suggests that more than one of these or other readings could be a part of Heng’s vision.

Heng’s “The Rememberers” is gripping and troubling and as part of the wider collection from McSweeney’s, argues for an increasing acknowledgement of culture (through memory, stories, and interpersonal connection) in the systems disrupted by climate change.